A painting by Empson of his girlfriend, Haru.

And that’s that. You never see the text again. For the year is 1948 and there are no such things as USB memory sticks or cloud computing.

That was what happened to William Empson, the modernist poet and author of the seminal work of literary criticism, Seven Types of Ambiguity. Yet the story does have a happy ending—or at least a bittersweet one. Long after Empson’s death in 1984, the manuscript miraculously appeared amongst a set of papers donated to the British Museum.

In 2016 The Face of the Buddha has finally been published in a handsome edition that includes many of Empson’s own photographs. And the introductory essay by Myanmar-based scholar and poet Rupert Arrowsmith is a tour de force of scholarly insights.

“Not a burglar, but a university professor”

Empson arrived in Japan to take up a teaching job in 1931, mere months before the Manchurian Incident set the country on the course to war. Like any 25-year-old fresh-off-the-boat teacher with no knowledge of the language or culture, Empson had difficulty integrating.

As biographer John Haffenden relates, there was trouble on his very first night. Following a drinking session, Empson returned to his hotel after the doors had been locked. Undeterred, he clambered, legs first, through a nearby window only to find himself in the staff room of the adjacent station.

“Once caught, it was not a burglar, but a university professor”, ran the headline in the next day’s Asahi.

Empson’s first house was in Kojimachi, near the British Embassy. This allowed him to associate with the great Japanologist Sir George Sansom, who held the post of Commercial Counsellor. After a year, he moved to Takanawa.

Although disturbed by the increasingly tense political atmosphere, Empson revered traditional Japanese arts. He had read Waley’s translation of The Tale of Genji while at Cambridge and soon developed an affinity for noh drama. As Haffenden writes, “the noh, he believed, chimed with the philosophical ‘notion’ informing much of his own poetry—that ‘life involves maintaining oneself between contradictions’”.

Asymmetry and ambiguity

His poetic output was affected, too. In Empson’s 1940 collection, The Gathering Storm, three poems appear that are credited to “C. Hatakeyama (transl. W. Empson)”.

For many years nothing was known about “C. Hatakeyama”, and there were doubts whether such a person even existed. In the late 1990s, however, poet and literary scholar Peter Robinson uncovered the history of Chiyoko Hatakeyama, an obscure but talented poet who was living in distant Aomori Prefecture at the time. Though she met Empson only once, they corresponded for several years.

Hatakeyama wanted to write poetry in English but, instead, her famous sensei took her English translations of her Japanese poems and reworked them for publication. Empson also acquired a girlfriend, Haru. His relationship with her is the subject of the fine poem Aubade.

Much of his spare time was spent visiting temples in Tokyo and Kamakura, where he took painting lessons from the British wife of Junzaburo Nishiwaki, one of Japan’s leading poets of the 20th century. “The Buddhas”, he declared to a friend, “are the only accessible art I find myself able to care about”.

It was on a jaunt to the ancient capital of Nara in the spring of 1932 that he experienced the epiphany that led to the writing of The Face of the Buddha.

When he viewed the 7th century wooden statue known as the Kudara Kannon at the Horyu-ji temple and the Miroku Bosatsu at the neighbouring Chugen-ji nunnery, he was immediately struck by the profound beauty of the statues.

Furthermore, there was a feature, unremarked in any of the scholarly literature, that leapt out at him. The faces of the statues appeared to be asymmetrical, reflecting two different mental states. The left side, with its flat eye and mouth, conveyed detachment; whereas on the right side the eyes and mouth slanted upwards, conveying force and charm.

Empson was to find similar asymmetry in other early Buddhist statuary, in Japan and elsewhere in Asia. Being knowledgeable about contemporary science, he sought to relate his discovery to emerging theories of left/right brain functions.

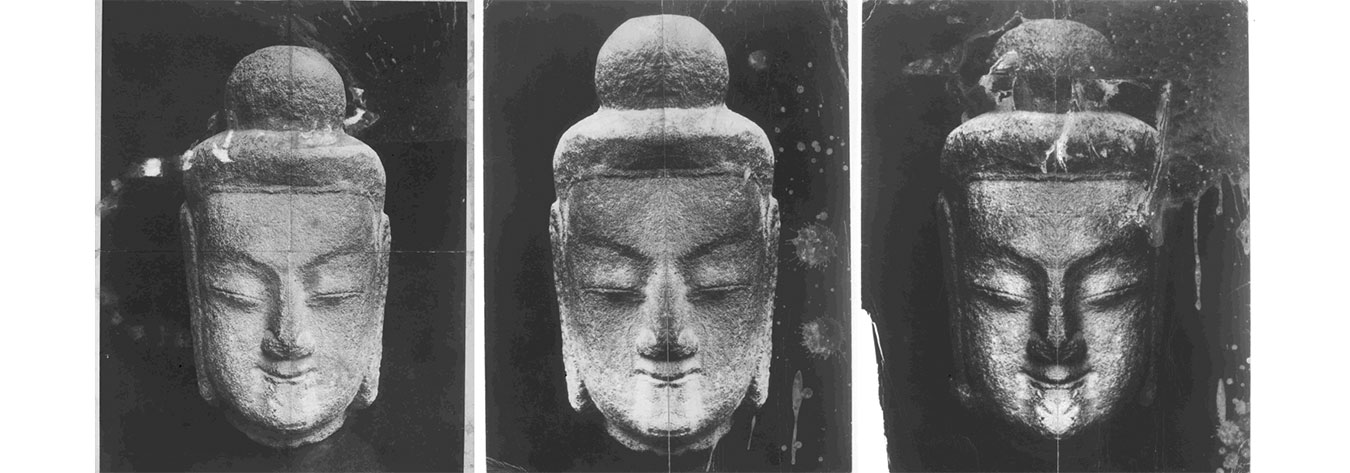

Some of the most interesting illustrations in The Face of the Buddha are Empson’s own manipulated images of the statues’ faces. By doubling the left side and doubling the right side of a face, he gets drastically different expressions. The man who revealed different layers of meaning in the poetry of Shakespeare and Donne had identified the same principle at work in the Buddhist statuary of the 7th and 8th centuries.

Ambiguity, contradictions and complexity were the leitmotif of his work, and also his life. According to Haffenden, it was an episode of sexual ambiguity that led to his premature departure from Japan. A life-long bisexual, Empson appears to have propositioned a taxi-driver, who reported him to the police.

The older Empson went on to greater things—a knighthood and further renown as an academic and literary critic. He never set foot in Japan again, but the influence of his Asian experiences was profound. He prefaced his Collected Poems with an extract from his own translation of The Fire Sermon, a Buddhist text. It was also read out at his funeral in 1984.