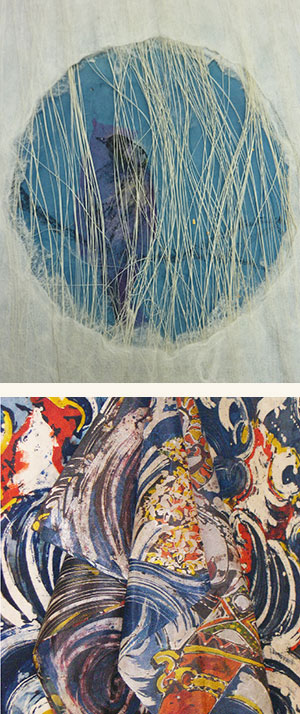

Elaine Cooper uses washi to make original and innovative artwork.

Thought to have been perfected in the 8th century, the making of washi (Japanese paper) is one of Japan’s most traditional crafts, passed down in families from generation to generation. But Welsh artist Elaine Cooper has broken with that convention.

Welcomed into the exclusive community as an apprentice washi-maker in 1991, her creations sell in the UK and are attracting attention from buyers in Japan, too.

A fine arts graduate from the Maidstone College of Art in Kent, Cooper first made paper for her etching work. These sheets were made using fibres from cotton and vegetables.

She had her first experience of washi and washi-making in 1991, as a volunteer during a UK nationwide Japan Festival. Her task was to explain the washi-making process demonstrated by artisans attending from Mino City in Gifu Prefecture.

“Although I couldn’t understand Japanese—all I had to draw on was my own experimentation, reading of books, and observations of how they made the washi—it all started to fall into place”, Cooper told BCCJ ACUMEN. “The artisans and I had such a connection; it was quite incredible”.

This encounter resulted in Cooper receiving, and accepting, an invitation to study in Mino with Akira Goto, a washi master, who began making the paper when he was six years old. “I jumped at the opportunity”, Cooper said. “It was like a dream come true. The washi—so thin and translucent—gave me ideas for what I had been trying to do with my work: overlay paper.

Although Cooper planned to stay three weeks and return to the UK to develop her work, her arrival in Japan marked the start of a 10-year apprenticeship.

“I fell in love with not just the craft, but the entire cultural heritage that surrounded it: the people and the environment. That influenced me immensely and I was able to create, learn and study”.

While Cooper says it took four years of intense work until she could make washi to a high standard, the effort has certainly paid off. Now, based in the creative area of Spike Island, Bristol, she not only creates and supplies washi to artists, interior designers and the fashion industry, but also sells the artwork, lighting and architectural installations that she makes using that washi.

Elaine Cooper gave washi-making demonstrations at a Japan festival in the UK in 2001.

In terms of future growth, she is in discussions with a retail wholesaler. Her plan is to launch a website by the end of 2015 featuring her as a supplier of paper-making tools, equipment and materials, building on sales of her hand-made paper-making frames.

Cooper attributes the success of her business to her colleagues in Mino. One of only three washi-making areas in Japan, Mino is recognised as a centre for the Craftsmanship of Traditional Japanese Hand-made Paper, and was included on the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in November 2014.

The majority of local people are involved in the craft, from cultivation of the raw materials to the creation and promotion of washi.

In practical terms, her colleagues source and store the fibres and equipment required for the washi-making process until she is ready to receive it. Artistically, too, they are on hand to offer support. This includes regularly checking her skill when she is in Japan.

“If I have an idea for paper, I speak to my sensei (teachers)”, she said. “I’m very lucky that I have that assistance if I need it, and it’s nice that they ask my advice as well”.

Such was the inspiration from Cooper’s innovative work while in Japan that Goto developed paper—that is on sale in Tokyo—using a mix of Western and Asian sheet formation techniques.

This fusion of East and West is evident in much of Cooper’s work, too. And, despite having nearly 25 years’ experience in the craft, she, like Goto, is still striving to create distinctive and leading works. As she once dreamed of doing, she can now fuse more than 500 layers of washi to make overlaid paper and is maintaining her skill to make sheets as light as 6g each.

“Washi is so much more than a surface. Complex, tactile and beautiful, it is the art”, she said. “For me, the texture, colour and finesse of the paper are as vital to a composition as the image that it finally portrays, so the artist and paper are connected, and the image and paper become one.

“Having complete under-standing and control of the processes allows me to create complex textural effects and images. Just by knocking the frame against the side of the vat, I can create undulating motions that can create wave patterns within the sheet”.

Unlike paper made using Western sheet formation techniques, washi is extremely versatile, strong, malleable and absorbent, allowing it to be printed, dyed, painted, stitched and spun. According to Cooper, its versatility provides artists with an ideal raw material; the only limitation is an individual’s ideas.

But washi-making is physically demanding and requires a number of painstaking processes that take 19 days from start to finish.

This has resulted in the decline, over the past 30 years, in the number of those making the paper, together with a surge in the production of machine-made washi.

“At one time, there was a very real danger that the papermakers’ craft would be lost within a generation”, she said, adding that the art is now bouncing back.

That is in no small part thanks to the efforts of Cooper herself. Her work has raised the profile of the industry in Japan and the UK. She gives talks and organises workshops at British colleges and, in 2001, arranged 14 washi-related events in England and Wales attended by her colleagues from Mino. In 2002, she received a commendation from Masaki Orita, then-Japanese ambassador to the UK, for her contribution to Anglo–Japanese relations, and was featured on Asahi TV in 2014 for her work in the industry.

“Running alongside my long-term business plan is work to continue promoting both the art of washi, and the ways it has had immeasurable influence in Japan, both culturally and economically”, she said.