“This is not an economy that is always easy to penetrate, but you have to stick at it for the long term”.

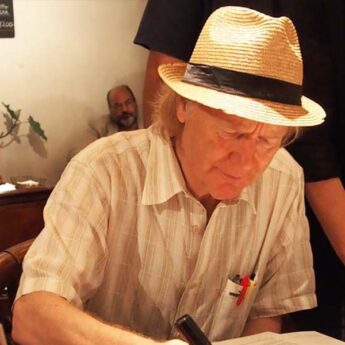

Lord Green of Hurstpierpoint, appointed minister of state for trade and investment in January, has been a frequent visitor to Japan for many years. He was last here in late October for a series of meetings, including ones with Yukio Edano, his new counterpart at the Ministry of Trade, Economy and Industry.

Curriculum Vitae

Stephen Green began his career with the Ministry of Overseas Development before joining McKinsey & Co. Inc. in 1977 and undertaking assignments in Europe, North America and the Middle East. He joined The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp. in 1982 and was made group treasurer of HSBC Holdings in 1992. Lord Green became chairman of the British Bankers’ Association in November 2006, was elected deputy-president of the Confederation of British Industry in May 2010, and in July of the same year became vice-chairman of the International Chamber of Commerce.

How would you characterise the present UK–Japanese relationship?

I believe we are closer now than we have been for some time. It was striking the way in which a lot more British companies suddenly took a new look at Japan in the wake of the disasters of March, out of sympathy and respect for the way Japan and the Japanese people responded. There has clearly been greater interest among British companies in Japan.

How long might that last?

How long might that last?

I expect the increased interest to be converted into business opportunities, and it is the task of the UKTI office here to take advantage of that. We now have a new government, a new prime minister and a new minister of trade and industry, all of whom want to make Japan more flexible and responsive to global economic trends.

What are the biggest challenges facing the two nations?

In trade relations, there are many barriers to the Japanese retail market that make it difficult to enter, or expensive to do so. That cost is then passed on to the Japanese consumer. Freeing up trade would be of huge benefit to the Japanese people. The minister indicated that was clearly the direction in which they are moving.

Why are Japanese firms increasingly setting up in the UK?

Japan is a very prominent trade partner for us. The role of Japan in pulling the British car industry onto its feet and instilling pride in the output is understood by all. British people say with pride that Nissan’s factory in Sunderland is the most efficient in Europe, and that we are now exporting Toyota cars to Japan. [This pride] may be less visible in other industries, but it is there as well, as in the area of renewable energies. Our high streets have Uniqlo and Daks, which most people do not know is owned by a Japanese company. So there is quite broad-based Japanese investment in the UK economy. Companies know there is no political risk associated with Britain, and that it is a predictable, reliable environment for them. We are open—and have had a long-standing openness—to foreign investment which, in the UK, stands at 52% [of all investment], and 22% in the US, but only 4% in Japan. Those statistics alone say something about the openness of Britain’s economy. We should also do more for the tertiary education sector, as there are some 400,000 foreign students in UK tertiary education, but [by comparison,] not enough Japanese students—only 4,170, according to the British Council here.

How can more UK firms be encouraged to invest in Japan?

There are nearly 500 UK firms here and that is fewer than we would like, but it is not always plain sailing in this market. Tesco, for example, has recently withdrawn from Japan. This is not an economy that is always easy to penetrate, but you have to stick at it for the long term. Unilever, for example, has been here for nearly half a century. A company needs to be present over a long period of time and, while that is important in all markets, it is especially so here in Japan.

How might the Japanese authorities help?

In the context of the EU trade negotiations, significant progress needs to be made on non-tariff barriers, particularly sectors where there are opportunities for UK exporters and Japanese consumers, such as in the pharmaceuticals and medical-devices sectors. Those are areas that would benefit the Japanese consumer and examples of regulations that impede care for Japanese people.

What are the implications of recent events at Olympus on Japan-UK relations?

I don’t expect any broad implications for Britain and Japan, but this is clearly an issue that is important to the Japanese prime minister, who has said there is a need to ensure that there are high corporate standards in major Japanese businesses.

What does Britain hope will result from the scoping exercise for a free trade deal between Europe and Japan?

The negotiations between the European Union and Japan are extremely important to both sides. Any trade agreement that is worth having is going to be difficult to achieve. I have been involved with another FTA—with India—and, although the issues are different, the one thing both have in common is that they are difficult to achieve.

There has been much in the papers recently about the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal. At your meeting today with the trade minister, did you sense a desire to make the ETA with Europe work?

Yes, absolutely. We did not talk in great detail about the TPP, but there was no indication that this is an either-or matter. He considers both equally important.

Do you believe the euro is on the brink of unravelling?

While I don’t see it unravelling, the situation is very complex and we’re certainly not out of the woods yet. The agreement that was reached at the end of October was very important. The underlying items towards which we need to work include fiscal consolidation across the eurozone that would prevent this kind of situation emerging again in five or 10 years’ time. There are plenty of challenges that have yet to be faced in the eurozone but, at the end of the day, I do not believe the situation will unravel or implode. Recent commentaries overlook two things: the sheer political will to make the zone work; and the technical difficulties of getting [even] one of the smaller countries out of the eurozone. It would be extraordinarily difficult and unbelievably expensive. To completely dismantle the entire thing would be like a huge earthquake. What they will do is muddle through, and it is likely that this will involve diminished economic prosperity in the near- and mid-term, but we are not looking into an abyss.