When Emiko Jozuka dived into her father’s archive of 300,000 photographs, she found herself sifting through five decades’ worth of incredible automotive heritage. In 1966, Joe Honda launched an international career photographing everything from Formula One and NASCAR to Motocross and the Paris-Dakar rallies.

As the first Asian to document this scene, Honda acted as godfather to motorsports photography in the continent, fuelling interest in Japan, where the sport had previously been almost unknown. In 2017, Jozuka established an initiative focused on conserving Honda’s vast archive of 35mm film photographs and sharing it with a broader audience.

This December, she will hold an exhibition, supported by Tokyo-based award-winning professional photography atelier Shashin Kosha, at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan to celebrate Joe Honda’s legacy. ACUMEN spoke with Jozuka, a CNN journalist, about her 80-year-old father’s art and her vision for it.

How did you start archiving your father’s work?

How did you start archiving your father’s work?

I grew up in a flat that was strewn with all these photographs and would hear my parents talking about car brands, drivers, dates and motorsport jargon that meant nothing to me. Understandably, my father didn’t want to pull me into that world, and I initially dismissed it as a boring, male-dominated industry. Because he was so modest, I was also oblivious to the huge impact he’d made on the automotive and photographic community. He was always just ‘dad’ to me.

After graduating from university, I spent two years in Turkey reporting on everything from art and politics to conflict and human rights. Once I came back to the UK, I found I had a new perspective on things that had once felt familiar—my father’s art for one. I realised he’d acted as an influential interpreter of the automotive industry. Most importantly, he’d used motorsport culture as a means of expressing his creative vision. Appreciating that made me eager to know more about the people, culture and technology portrayed in the images, and my father’s artistic practice.

Why is his work important?

Honda was the first Asian photographer to capture the international world of motorsport and present it to audiences in Japan, where the sport gained a devoted fanbase. But, beyond that, his archive travels from the grit and glamour of motor racing’s golden years through its evolution into a technological arms race funded by big business. The cars were only ever one part of a larger human narrative he wanted to tell. His images range from the visceral to the purely functional—immortalising the raw experiences, memories and developments of the international world of motorsport at a pivotal moment in history. The archive gives a unique perspective on his life of global adventure and how technological changes impacted both the photographic medium and the motorsport industry over the past five decades.

Honda experimented with blur effects and nature to create images that reflected his love of Impressionism. (France, 1972) Photo: Joe Honda

What is the Joe Honda Initiative and its mission?

In 2017, I founded the Joe Honda Initiative to reanimate his memories and legacy—one photograph at a time. In the short term, we aim to preserve my dad’s artistic endeavours, introduce them to new audiences and attain much-needed support to catalogue and conserve his life’s work and legacy. On this front, my work with the Initiative has already allowed me to collaborate with many inspiring people. For example, Takuji Yanagisawa, president of Shashin Kosha, has been advising me on the planning and logistics of executing an exhibition. The long-term goal is to establish a foundation that democratises access to motorsports, photography and art.

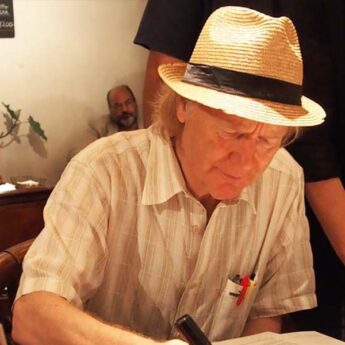

Photo: Emiko Jozuka

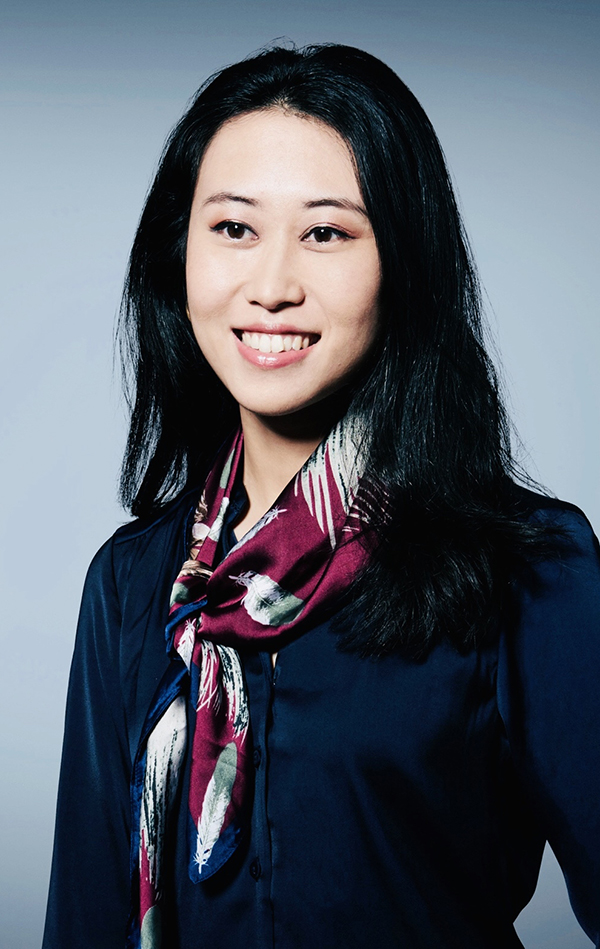

Joe Honda

During a five-decade career, Honda dedicated himself to photographing motorsport around the world, including Formula One, NASCAR, Motocross and the Paris-Dakar rallies. He is now recognised as Asia’s godfather of motorsport photography and journalism, and is credited with igniting widespread interest in motorsport in Japan. In 1968, he became the first Asian representative of the International Racing Press Association (IRPA). Honda’s eclectic style draws inspiration from sculpture, graphic design, French Impressionist painting and documentary photographers such as Eugene Atget and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He has published dozens of books on the history and politics of the automotive industry and exhibited in prestigious galleries such as the Canon and Nikon salons.

What aspects of Honda’s archive have you found most interesting?

As a Japanese person who grew up in the UK, I have always welcomed anything that helped me get more deeply in touch with my native country’s history. My dad’s career paralleled the rise of Japan’s economy and the entrance of Japanese manufacturers and firms onto the international stage. It’s been fascinating to see their influence and how different business players worked together to advance the motorsport industry. Interestingly, in the 1980s and 1990s, camera manufacturers such as Olympus and Canon were major sponsors of F1 teams, their logos displayed across the car’s livery.

My father’s photography also brings to life the relationship between Japan and the UK in Formula One. He documented automotive manufacturer Honda Motor Company Ltd.’s first forays into F1—shots of British F1 driver John Surtees driving Honda Racing’s RA300 F1 car in 1967 and working alongside Honda engineers in the paddock area. I even found a close-up shot of Prince Charles speaking with one of the drivers. I’d love to find a space to showcase those stories in the future.

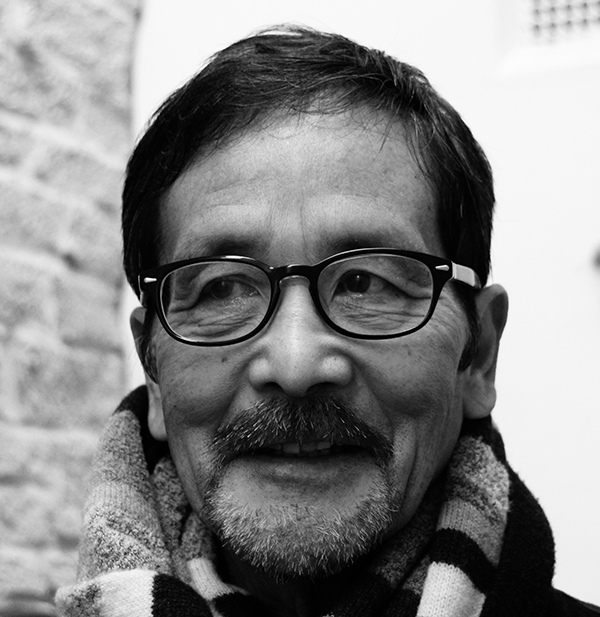

Honda (center) flanked by International Racing Press Association President Bernard Cahier and Jack Brabham OBE.

What intrigues you about the automotive and motorsport industries today?

The automotive industry is a world away from what it was when my dad started documenting it in the 1960s. When I reported on the Singapore F1 last year, I was struck by the contrast between today’s slick formal press conferences and my dad’s images of drivers in the 1960s hanging out in their garages with members of the press before the races. The informality of those days is gone.

On the plus side, we’ve seen British six-time F1 World Champion Lewis Hamilton push the needle on sustainability and diversity in the sport. There are many more women in leadership positions within F1 and the automotive industry, shaping its future. Ultimately, I’m most interested in understanding motorsport’s legacy and connecting the dots between its past, present and future. As for the automotive industry, beyond the latest models, what’s fascinating for me is how this particular mode of transportation has evolved over the decades, shaping cultures, human societies and urban landscapes along with it.