First interview with Japanese literature expert since becoming citizen of Japan at age 89

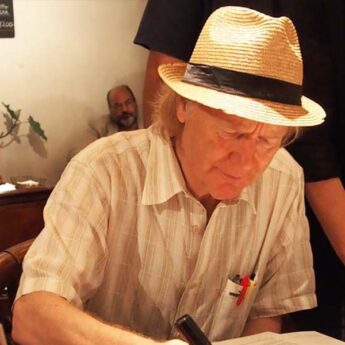

It’s pretty difficult to get an interview with Donald Keene these days. I owe my good fortune as the first foreign newsman granted an interview after he obtained his Japanese citizenship on 8 March to longevity and reticence on my part.

I have simply never requested an interview in the 40 years that have passed since we were introduced, in the summer, by Yukio Mishima. The occasion, a dinner for three at the seaside resort of Shimoda, was organised by Mishima, the author, poet, playwright, actor and film director who performed ritual suicide by disembowelment (seppuku) after a failed coup d’état in November 1970.

Donald is, above all, a man who loves life. I remember accompanying him to a performance by the Bolshoi of the opera, Boris Godunov. It was in the autumn of 1970. Mishima was there, wearing an all-white suit. Spotting him in the intermission Donald gave a little leap of joy and shot through the crowd to greet his friend.

Forty years later, he rejoices in having become a Japanese; that’s the thing. The horror of 11 March 2011 and the spectacle of foreign businessmen rushing to Narita International Airport gave Donald the opportunity to express his long-held passion for Japan and things Japanese by becoming Japanese.

Following the interview with Donald here on the first anniversary of the earthquake, I sped to my bookshelves to dig out books of his that we spoke about during our 40-minute chat.

So here is a short list of the books that the maestro chatted about during our interview.

First up came Essays in Idleness. Donald recalled when and where he completed this translation of notes and jottings written by the monk Kenko Yoshida between 1330 and 1332, and all lined up in numbered paragraphs for ease of reference.

“I was up in Karuizawa and it was the rainy season, and there were no visitors to disturb me”, he recalled. This was in the mid-1960s and the book was first published in Donald’s translation in 1967 by Columbia University Press. Donald dedicated the work to his close friend, the late Ivan Morris, also a professor of Japanese studies at Columbia. Donald has never married and, as a married man, I have long chuckled over item 190 by the trusty Buddhist priest. It begins with a flourish: “A man should never marry”. What follows is delicious. Dig it out!

Next we spoke of Donald’s monumental biography of the Emperor Meiji. This work, titled simply Emperor of Japan, runs 922 pages including the index. It weighs a ton. Donald, for all his feistiness, might have found his masterpiece a bit bulky in the handling. The author starts his narrative in the years before Meiji was emperor, hence his subtitle “Meiji and His World, 1852–1912”. It is a tremendous read for all the copious detail.

I asked Donald about that part of his rip-roaring narrative that touches on rumours and reports that Meiji’s father, Emperor Komei, died from poisoning by arsenic, possibly administered by a lady at the imperial court in Kyoto (The very idea! The assassination of an emperor!). Had he experienced any reactions from the right, I asked? Donald responded that, basically, he had been left alone to get on with his scholarly pursuits, touching on the facts. One day–early on in the research—two heavy-set men had called on him. “They were yakuza”, Donald said, “but they never showed up again”.

As a third tome, Donald and I settled on his 2008 venture into autobiography, titled Chronicles of My Life: An American in the Heart of Japan, also published by Columbia University Press. Here, let me observe that Donald is a man with strong convictions. “I am a pacifist”, he said. His work merits attention from that point of view—so rare in a US Navy officer.

In a graphic scene, he depicts his mother’s reaction when he reappears at home in New York after years of action in the Pacific during World War II. To show his mother, Donald—assigned to where he could use his Japanese language skills—pulled out of his bags a souvenir of the war: a samurai sword. His mother let out a shriek of horror and Donald retreated.

Here is a man who is not afraid to make fun of himself and whose memoirs take off on that note. See page 69 for a classic exchange between Donald and the late (Lord) Bertrand Russell, in which the latter questions Donald about his love life.