After two decades since his last visit to Tokyo, Peter Wynne Rees cannot wait to see how the face of the city has changed.

And while he insists that he is no expert on the urban planning and design of the Japanese capital, he will surely be running his seasoned eye over its lines and curves, its spaces and constricted areas, its modern tower blocks and the low-rise residential districts.

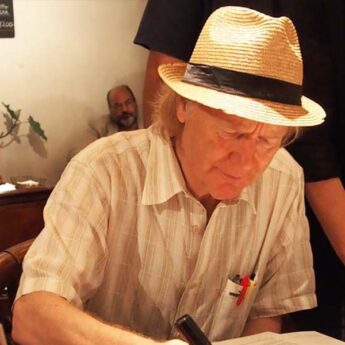

After 29 years as the chief planning officer of the City of London Corporation, a position he left last year to become professor of places and city planning at University College London, Rees has an unerring eye for what works and what falls flat.

“I think that in Japanese culture, there is a fundamental understanding of the need to retain the important elements of historically important places”, Rees told BCCJ ACUMEN.

“Japan has no problem with having old and new buildings sitting together and there is no desire—thankfully—to clear entire areas of cities, as some others do”, he added.

“In that way, I think that Japan and Britain are quite similar”, 66-year-old Rees said.

“In London, we have kept the best of the past and we try to approve the best new buildings. I believe that is the way to create a successful future, although it must be remembered that city planners do not make ‘real places’; it is the people who make a city”.

Rees will be visiting Tokyo on 20 and 21 May to address MIPIM Japan, the global real estate forum that will be staged in Japan for the first time.

He will speak on the topic of “Density: Innovative solutions for liveable cities” and draw heavily on his experiences helping to transform London into a city that is welcoming to business as well as to its residents.

Bringing together property and finance professionals from around the world, and recognised internationally as the prime forum for all property asset classes—from office through retail, residential, infrastructure and leisure—MIPIM Japan will include conference sessions and networking opportunities over the two days.

The event will focus on four key themes: the Olympics, inbound and outbound investments, innovative cities and tourism. The speakers will include Ken Livingstone, former mayor of London, and world-renowned architect Kengo Kuma.

“Very early on in the battle, we realised that if we wanted London to retain its title as a centre of world finance then we needed to compete on quality rather than quantity”, Rees said.

“It’s about how pleasant a place is to live and work in; it’s not about how many thousands of square feet can be built on”.

While Dubai and Frankfurt were following the US model of throwing up ever-taller skyscrapers, London resisted that approach for as long as possible.

The result was that in the decades that Rees oversaw the development of The City, it evolved from a place that became a ghost town—both after the last office workers had left at the end of weekdays, and at weekends—to the thriving and energetic district it is today.

London remained committed to redeveloping redundant derelict spaces—such as the Broadgate project close to Liverpool Street Station—until there were no options other than to build upwards, said Rees. But even then, the greatest care was taken with new developments.

“If we were going to build tall, then it was important that these structures were of the highest quality in terms of architecture and planning”, he said.

A conscious decision was also taken to build a tight cluster of tall buildings in the eastern part of the city, well away from historic landmarks such as St. Paul’s Cathedral—assets that Rees considers to be among the city’s unique selling points.

The result is tall buildings of high quality that are a complete contrast to what he describes as “drab, ’60s-style architecture”.

And Londoners have embraced them, going so far as to give them interesting nicknames, which include The Gherkin, The Cheesegrater and The Walkie-Talkie, because of their distinctive shapes.

Asked about his favourite part of London today, Rees unhesitatingly identifies Paternoster Square, the space alongside St Paul’s Cathedral that was developed by Mitsubishi Estate Co., Ltd.

Replacing the 1960s development that had stood there before—and was composed of raised, grid-plan space surrounded by buildings all constructed in an identical, monotonous style—is “a very fine, modern space alongside our most important landmark”.

Complemented by cafés, sheltered areas and enclosed by buildings by various architects and in different styles, the area has been transformed.

“It’s a room in the city where people can go to relax and it gives me great pleasure just to walk through that space—I feel like I’m at home”, Rees said.